There is no doubt that technology has significantly improved the way clinical trials have been run over the last few years.

To date, these improvements have mostly been focused on the trial process – including electronic databases, computerised trial management and collecting data from patients using smartphones and tablets. This has brought great benefits and efficiencies around study conduct, analysis and data management, and formed the framework of modern trials designed to understand the safety and efficacy of new treatments.

We are still in the very early stages of determining to what extent wearable technology and sensors will transform drug development and what the true potential might be, but they are already offering the promise of allowing us to do completely novel assessments, both through improved insight into the patient experience and providing a vast set of new observations and learnings.

Fully understanding the patient experience in a trial is vital, and wearables are able to monitor both the physiological impact of a treatment and track the progression of a patient’s symptoms to a level we’ve never previously been able to get to. Wearables are offering a new stream of data alongside traditional questionnaires that attempt to measure outcomes.

However, there are a number of considerations to take into account when it comes to incorporating wearables and sensors into clinical research.

Data, context and measurements

Measurement of physiological variables has always been central to the assessment of the safety and efficacy of new treatments. Wearable technologies have drawn greater focus to the potential of the individual patient-level physiological data within trials, expanding our attention away from the conventional assessments.

Batteries of questionnaires that ask patients to provide information on their subjective experience raise difficult questions about what it is we’re actually measuring. Attempting to measure vague concepts, such as asking a patient to rate their pain, is fraught with complications as there is no widely accepted objective measure of an individual’s experience of pain, for example.

The intense interest in wearables and sensors in clinical trials has to a large extent been driven by the idea that we can standardise and offer a more “objective”, round-the-clock measure of the range of patient experiences. Despite not yet being able to record and standardise pain, it is this passively sourced data that provides us with alternative levels of insight into their experience and medical condition without the patient needing to divert from their normal day-to-day life.

Clinicians widely recognise that questionnaires are only a snapshot in time of the patient’s condition. However, at present, these same clinicians are also still trying to determine what the data from wearables actually means in context of the modern clinical trial. For example, Fitbits and Apple watches seemingly provide simple measures in step count from a patient, yet these devices are not measuring actual steps but producing calculations based on their movement through space. All of these devices have their own algorithms for converting the physical feedback the devices are receiving into a measurement of steps.

So, it raises the question: can a clinician be confident such wearables are consistently giving accurate measurements, and more fundamentally, what does this data actually tell us in understanding the effect of a treatment?

Regulation and changing roles

There is ongoing discussion as to whether wearables offer the correct measurements and insights into what is meaningful for the patient.

Just because, for example, a patient’s step count has increased 20% over the course of the study, does that actually matter to the patient? Regulators and clinicians do recognise the significant potential of the use of wearables, but regulatory bodies in particular have been very clear in advising that trials need to start by determining what will be measured before implementing the use of a wearable device. Just because we have the technology, it does not mean it’s necessarily the right tool for a given job – simply asking a patient how they feel often remains the best way to gain an insight into their experience. But wearables open up new and potentially very fruitful avenues for us to explore, supported by the more traditional subjective assessments.

However, wearables also create additional logistical variables. What was originally a couple of data points recorded in a daily diary has now evolved to a wearable product that can produce gigabytes of data in a single day. From a technical and logistical point of view, handling and analysing this data in a regulatory compliant way is a whole new challenge for the sector. Huge responsibilities are now imposed on vendors and sponsors by the inflow of potentially very sensitive data now produced by patient wearables.

Patients’ familiarity with similar technologies in their daily lives has definitely brought a willingness on the patient side to adopt wearables in relation to medical treatment, which holds significant promise for the healthcare industry. Electronic clinical assessments are going to continue their upward trend and adoption, and advance conversations around decentralising and virtualising trials. Wearables even hold the possibility of conducting remote performance outcome assessments, allowing us to shift more tasks out of the clinic.

“With the impact of COVID-19, tech corporations are likely to accelerate their move into healthcare in general”

The role of the modern trial clinician and the patient is set to be transformed as pharmaceutical organisations become braver in utilising and integrating these technologies into clinical research.

The future shift

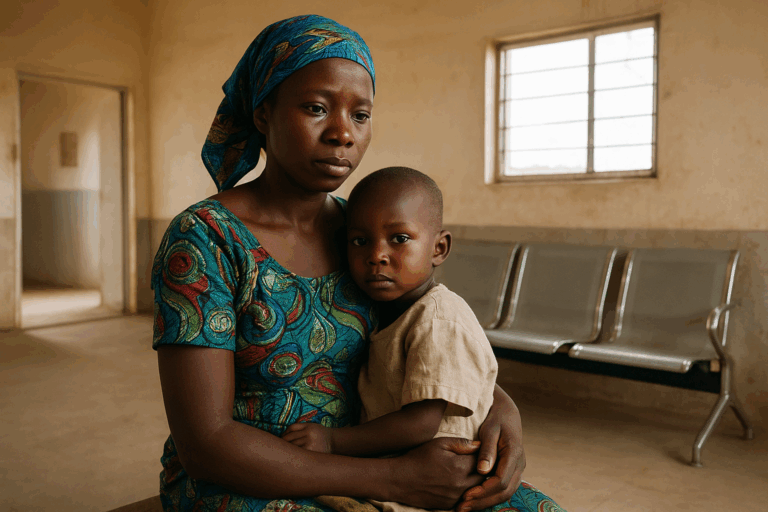

There are a number of ongoing industry projects involving sponsors, vendors and regulators, to try and understand how best to leverage wearables and sensors in clinical trials. Amid the excitement of using new technologies, a key theme that keeps emerging is the importance of not losing the human connection during a clinical trial – if the impact of a disease or treatment is particularly difficult, the face-to-face interaction with physicians may be really meaningful and important for patients.

Regulators are actively requesting sponsors to come up with useful and experimental approaches to using wearables, and encouraging open discussions on planned uses of these devices. As we continue along this upward trajectory, we’ll likely see more of an open landscape for big tech companies like Amazon, Google and Apple to get involved in this space.

With the impact of COVID-19, tech corporations are likely to accelerate their move into healthcare in general, particularly as Amazon shifts from being a consumer marketplace to an essential logistics distributor. This is positive as it means an influx of investment and innovation into the sector, and important lessons can be learned from their more consumer-focused work on developing solutions that are easy and a pleasure to use. However, these companies are used to rapid timelines that are drastically different from the longer timelines in healthcare and drug development that often span the course of years rather than months.

As the capabilities of wearables progress, we are set to see the continued involvement of consumer technology in the healthcare space. Wearables hold the potential to both improve patient experiences and our understanding of that experience, but the sector must appropriately determine and navigate how best these vast data sources can inform clinical decisions. More so, the pharmaceutical sector and regulators must continue to actively collaborate and foster discussions on best practices as these innovations are only set to continue.

Paul O’Donohoe is the Scientific Lead in eCOA and Mobile Health at Medidata, where he is responsible for providing strategic oversight of the development of Medidata’s electronic clinical outcome assessment technologies, and supporting internal teams and partners around the implementation of industry, regulatory and scientific best practices in clinical trials using mobile health technologies.