“It is the single defining problem of our age.

That’s how strongly Douglas Johnson-Poensgen views the need for energy transition and for batteries to be produced more sustainably as part of that shift. A space where this need is felt most acutely is the need to make electric vehicles (EVs) more environmentally friendly by cutting out carbon emissions through the supply chain.

Johnson-Poensgen is CEO of Circulor, a leading provider of supply chain traceability and dynamic CO2-tracking which raised $14 million (nearly £10 million) in funding earlier this year. The blockchain company, founded in 2017 by Johnson-Poensgen and long-term business partner Veera Johnson, provides the only live solution in the market capable of carbon tracking. It works with enterprises across the globe and, most notably for this story, numerous prominent vehicle manufacturers wishing to improve their efforts in sustainability and responsible sourcing.

Some recent research by Circulor shows just how worrisome the situation in the sector has truly become – especially when it comes to electric vehicles. A lot of problems further back in the supply chain have been disregarded so much so that the carbon emissions across the life cycle of those EVs are often greater than that of many internal combustion engine vehicles, particularly diesel models.

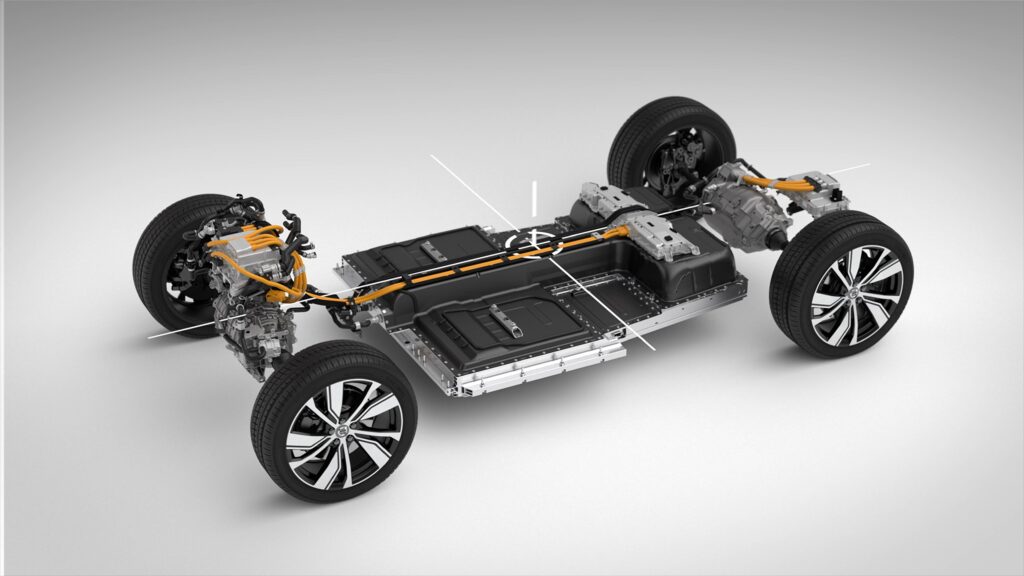

“We all believe that things like the move towards electric vehicles are clearly important in the journey to slow climate change,” says Johnson-Poensgen. “The problem, though, is that in order to create electric vehicles and the batteries within them, we are having to mine massive quantities of raw materials. Some of those raw materials cause significant environmental damage or require massive amounts of energy such as that which is needed to turn rock into batteries.”

Johnson-Poensgen, a former British Army Royal Engineer, has international experience spanning a quarter of a century working both in leadership roles for large corporates, as well as starting and growing companies. He is now channelling all of that expertise into Circulor.

He says: “This headlong rush towards ‘Let’s all have electric vehicles by 2030’ has meant that we’re ignoring some practical challenges like ‘How are we going to charge them all?’ and ‘Are we going to generate enough renewable energy or electricity so that we’re charging them with sustainable power?’

“As a result, the real challenge has shifted to the supply chain. Of course, these are complex industrial supply chains because the materials you start with are not the materials you finish with. And, traditionally, you’ve not really known your supply chain much beyond your tier one or possibly tier two supplier, certainly not back to tier six or seven, that is to say: all the way back to mining sites. Increasingly, our customers are asking ‘How do I get a greater level of visibility into my supply chain in order that I can start to manage this, that I can specify sustainability alongside price and quality in my decisions about who I buy from?’”

About 30% of the carbon invested in an EV comes from the manufacturer, although many are now moving to make their own factories carbon neutral. The other 70% comes from the supply chain, with half of that pertaining to the battery alone.

“We will end up making climate change worse if we can’t deal with critical issues in the supply chain,” Johnson-Poensgen says.

Amongst Circulor’s customers within the EV space are Volvo, Jaguar Land Rover (both of whom have invested in the company), Daimler and Polestar, who recently announced their desire to make a net-zero vehicle by 2030 – a colossally-bold plan which Circulor is looking to help them with.

“Polestar talks about us in the context of that target,” Johnson-Poensgen admits. “That’s a proper moonshot challenge because, actually, no one knows how to do that and yet, it’s a worthwhile objective. They’re doing it as a way of trying to drive top-line growth, so people are going to buy a Polestar and go ‘I buy into that, I want that’. It’s a hugely audacious goal and I admire Thomas [Ingenlath], the chief executive, for putting it out there.”

The distributed-ledger technology used by Circulor utilises a mix of blockchain, biometrics and machine learning to digitally verify the movement of materials at every step of the supply chain, right from the mining process through to the factory where the vehicles are made.

“We’re creating a digital twin for commodity to source, and then a digital thread that follows that material all the way to the end product,” explains Johnson-Poensgen. “And, based on that digital thread, we’re attaching other information to that flow of materials, including the amount of embedded carbon added by each participant to the supply chain.

“That’s the basic principle, and you can apply that to any number of use cases. You can apply that to the traceability of leather from cow to car, which is what we’re doing with Jaguar Land Rover; you can apply that to battery materials, which is what we’re doing with the likes of Volvo, Polestar, Daimler, and a number of other car manufacturers.

“There are two broad drivers for this from our customers’ perspective: one is responsible sourcing, ‘I don’t want child labour in my supply chain’, ‘I don’t want deforestation’, ‘I don’t want leather that’s a by-product from deforested bits of the Amazon, I want leather that is sustainably produced or possibly even recycled leather’ and also ‘What’s the embedded carbon in what I’m actually putting my vehicle as I drive towards net zero?’

“The other driver comes in relation to businesses funding their operations. Every big corporation needs to borrow money to fund its working capital and its investments. If you are paying too much for your money, it affects your bottom line. So, with institutional investors such as BlackRock’s Larry Fink finding boards based on a lack of ESG [environmental, social and corporate governance] performance and some of the big lenders like Standard Chartered and Deutsche Bank are looking for evidence of that to use their facilities, it makes a real difference.

“If it costs you more to borrow money than me, I’m going to be more competitive than you. That’s how sustainability or ESG is going to drive the bottom line, quite apart from the fact that it might actually help you sell more.”

Interestingly, Volvo Cars, despite the pandemic, grew sales during a time when most car manufacturers haven’t. The Swedish manufacturer reported the best first quarter in its history as the company’s global sales increased by 40.8% compared with the same period last year. Johnson-Poensgen believes that that indeed demonstrates how doing business sustainably is good business.

“Volvo has had journalists say to them, ‘Yeah, okay, we’ve seen the headlines about sustainability and responsible sourcing, prove it’,” Johnson-Poensgen says. “And they’ve shown dashboards from our platform and said to them, ‘Look, I know exactly where my cobalt’s come from’, ‘I know what the carbon footprint in the battery going into this particular EV is today’. People go: ‘Wow, that’s amazing!’ And that’s why they commissioned people like us to help them.”

Circulor started four years ago with a triple-faceted focus of “people, planet and profit”. Since becoming profitable at the start of last year, the company has grown rapidly, so much so that the board is considering another round of funding and then potentially going public at the beginning of next year.

But Johnson-Poensgen and his colleagues are staying true to the vision they started with as the business looks to scale up and make even more of a difference to sustainability globally. That is what a considerable portion of the recent investment money will go towards.

“I’m in business to try and make a real difference to the problems we’re grappling with and that means that we have to achieve scale,” he says. “We have to work with more car manufacturers in more polluting industries, for example, to expand the impact. You have to make the technology more accessible, easier to engage with, etc.

“Clearly, all successful technologies go on this journey, so part of the investment will be spent on trying to take something that a bunch of pioneers decided was worth doing, and make it more and more accessible for the main body of car manufacturers so they go, ‘Yes, this is how we need to try and grapple with these things’, as well.

“We also believe that we’re in a sustainability arms race, in a positive way. There are a lot of folks trying to work on bits of solutions that belong in the overall drive to be more sustainable – but the challenge, of course, for customers, is ‘How do you see the wood for the trees?’ The planet needs us all collectively to get a grip of this pretty quickly. We know that what we’re doing as a company is something lots of people need and we want to place ourselves as part of the natural shortlist in people’s heads when they’re trying to grapple with these problems.”